The Unissued One Pound Note Forms of King Edward VIII

The appearance of several blank one pound notes in a series of auctions between 1980 and 2013 raised a number of questions - first among them for me was, just what are they?

Unexplained oddities such as these are one of the truly rewarding areas of Australian numismatics, a bit of legwork can go a long way in turning an oddball item into one that’s highly prized. These unissued one pound note forms draw in a number of different sections of Australian numismatics - specimen notes, error / variety notes, the switch from the reasonably large Harrison series notes down to the smaller Legal Tender notes, as well as the numismatic pandemonium that surrounded the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936.

The Life of King Edward VIII

Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David was the eldest son of King George V. His biographer has stated that “he was an intelligent child, with something of his father’s prodigious memory and an innate, wide-ranging curiosity which his parents failed to harness”. Edward was known to have been regularly abused by his nanny (who would pinch his face to make him cry just before meeting his parents), and as the eldest child, Edward bore the brunt of his father’s often “violently expressed wrath”.

In 1907, Edward was sent to the Royal Naval College at Osborne. Official reports are that while there, Edward was treated by his teachers and fellow students just as any other student. Rightly or wrongly, Edward himself however believed he was bullied. Despite early signs of his innate scholastic capabilities, Edward was regarded as being a poor student. One of his tutors at Naval College stated that “bookish he will never be”, and after two years of study it was decided Edward should be given a commission in the British Army.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Edward asked the Secretary of War for permission to serve in France. Lord Kitchener of course refused, and on the insistence of King George V, Edward was restricted to serving in staff appointments throughout WWI. Personal letters by the Prince that have been discovered in recent years showed him to be incredibly frustrated by not being able to fight alongside his fellow soldiers: “I hold commissions in both services and yet I’m not allowed to fight. Of course I haven’t got a proper job which is very painful to me and I feel I am left too much in a glass case.” After the war ended and much to the consternation of King George V, Edward kept up with several dangerous hobbies - steeplechases and aviation among them. His social life after the war was the subject of some discussion as well: ”In the army the prince developed an enthusiasm for nightlife, nightclubs, and dancing, which the style of post-war London life encouraged". Edward soon became a leader of fashionable London society, and after several affairs, he began a liaison with a Mrs Winifred (Freda) Dudley Ward, a mother of two young children who had separated from her husband. This relationship caused considerable embarrassment to the royal family, and also caused Edward’s relationship with them to deteriorate.

King George V attempted to keep his son busy throughout his young adult years by sending him on a series of royal tours to various parts of the Commonwealth. The prince’s rank, travels, good looks, and unmarried status gained him much public attention, and at the height of his popularity, he was regarded as being the most photographed celebrity of his time. His tours included visits to Canada, the United States, the Caribbean, India, Australia and New Zealand. Edward’s obvious popularity apparently made him increasingly vain. As one observer noted, he had “difficulty in understanding the symbolic nature of his position and tended to assume that the attention focused on him was a direct consequence of his own particular gifts.”

His father excluded Edward from discussions on political issues and instead urged him to find a wife and start a family. Edward refused and instead preferred to continue relationships with women that the king considered to be unsuitable. In 1931 Edward was having an affair with Lady Thelma Furness. On the 10th January, 1931, Furness invited Wallis Simpson and her husband, Ernest Simpson, to her country house at Melton Mowbray. Edward was fascinated by Wallis and it was not long before he was having an affair with her. His biographer has pointed out: “By 1934 the prince … saw Mrs Simpson as his natural companion in life … accustomed to getting his way when he knew what it was that he wanted, the Prince of Wales seems to have thought from 1934 onwards that matters would turn out as he wished. Though he appears from an early stage to have wanted Wallis as his queen, he made no effort to test or prepare the ground, even with those whose support would be vital. Neither the prince’s father nor mother seem to have raised with him either the consequences of the affair, nor its likely result. Thus the Prince of Wales’s affair with Mrs Simpson developed in “a political and constitutional limbo.”

Edward’s developing relationship with Mrs Simpson carried with it far broader implications than just the fact she was yet another married woman - a close friend of hers, Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe, was regarded as being a spy for Hitler’s Nazi government. The relationships between Simpson, Princess Stephanie, the German Ambassador to Great Britain and even Hitler were such that MI5 and MI6 had significant concerns that state secrets were being leaked from the royal household to the Nazis. Edward did not ease concerns about his ultimate loyalty when expressing his opinions about fascism and Adolf Hitler. A British diplomat recounted that at a party where there was much discussion about the implications of Hitler’s rise to power, “the Prince of Wales was quite pro-Hitler and said it was no business of ours to interfere in Germany’s internal affairs either re- the Jews or anyone else, and added that dictators are very popular these days and we might want one in England.” Whatever future objections there may have been from the Church of England regarding the morality of Edward’s relationship with Simpson, it is quite clear that the involvement of the future King of England with persons known to be associating with leading figures in the Nazi empire was completely untenable.

Following the death of King George V on January 20th 1936, Edward ascended the throne as King Edward VIII. On 16 November 1936, Edward invited British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to Buckingham Palace and expressed his desire to marry Wallis Simpson when she became free to re-marry. As king, Edward was the nominal head of the Church of England, and the clergy expected him to support the Church’s teachings. Baldwin informed him that his subjects would deem the marriage morally unacceptable for that very reason, and that the British people would not tolerate Wallis as queen. Edward then informed Baldwin that he would abdicate if he could not marry Simpson. Baldwin presented Edward with three choices: give up the idea of marriage; marry against his ministers’ wishes; or abdicate. It was clear that Edward was not prepared to give up Simpson, and he knew that if he married against the advice of his ministers, he would cause the government to resign, prompting a constitutional crisis.

In the face of these three difficult choices, Edward chose to abdicate - this was in fact the first time in history that the British or English crown was surrendered entirely voluntarily. Edward signed the instruments of abdication at Fort Belvedere on 10 December 1936, and on the night of 11 December 1936, he made a broadcast to the nation and the Empire, explaining his decision to abdicate. He famously said, “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Edward left for Austria the next day, and married Simpson in June 1937, after her divorce became absolute. With that, one of the most incredible chapters in the history of the British monarchy drew to a close.

The Prince of Wales and Australia

Australia was just one of the many far-flung corners of the British Commonwealth that the Prince of Wales visited on his Royal tours. Edward visited Australia between May and August 1920, his mission was to thank Australians for the part they played in World War I. The Prince of Wales was hugely popular in his time here - anecdotal reports show that when in Sydney, the queue of people to see him were the longest ever seen in Sydney. It is estimated that about 50,000 walked past the Prince that day, and that about 100,000 people were in the streets outside the Sydney Town Hall. The Prince’s appearances at all other locations throughout Australia drew similar crowds and adulation.

King Edward VIII and Australia’s Coins

The coinage of King George V was still being struck and issued at the time of his death in January of 1936, in fact the Australian economy was recovering so strongly from the Great Depression that the production of coins bearing the portrait of King George V could not stop if Australia’s increased economic activity was to be accommodated. Current research shows that discussions regarding new designs for Australia’s coinage, both obverse and reverse, began to take place around October 1936 - well after the accession of Edward VIII in January 1936, and just prior to his abdication in December 1936. The Australian Commonwealth Treasurer, Mr Richard Casey, announced on 15 October 1937 that "The question of coin designs has been under consideration for 12 months. It was considered that the appropriate time to change the reverse sides of the coins was when the obverse sides were being changed to carry the new King’s head.” With this timeframe in mind, we can see that plans for Australian coins featuring the portrait of Edward VIII would have been delayed, even if only for a relatively short period of two months, due to the new monarch’s intransigence as to how his portrait was to be shown on the coinage of the Commonwealth. King Edward VIII insisted that he be depicted facing left, specifically to show the parting in his hair.

While this may not seem to be an unreasonable request from someone always in the public eye, we have to keep in mind that it was British tradition that each successive monarch faced in the opposite direction to their predecessor. King George V was depicted on his coinage facing left, which meant that if Edward VIII’s wishes were obeyed, Edward VIII would have been the first British monarch in at least 500 years (since at least Edward VI in 1547) to face in the same direction as the monarch that preceded him. Research into the coinage of Edward VIII shows that “Several concerted attempts were made from the Mint to convince the King not to break with tradition, even including an attempt at portraying his left-side image facing right. In the end, the King’s wishes were followed and his proposed coinage portrayed his effigy facing left.” Edward VIII also apparently was keen for the coins of his reign to “exhibit modern reverse types rather than the more traditional heraldic approach.”

Whether the comments of the Australian Commonwealth Treasurer published in October 1937 are a consequence of the desires expressed by King Edward VIII is not known at this time. Regardless of the cause, Australia did indeed eventually receive updated reverse designs on it’s national coinage by 1938. Firm dates charting the development of these new reverse designs are not easy to come by, however what is known is that the Royal Mint at London did not begin work on preparation of the obverse and reverse punches (the tools required before dies can be prepared) for a revised Australian penny until the middle of April in 1937 - some 5 months after King Edward VIII had abdicated. As we can see from all of the above information, the reign of Edward VIII was simply too short for any meaningful progress to have been made on Australian coinage bearing his portrait - work was abruptly cut off very shortly after it began.

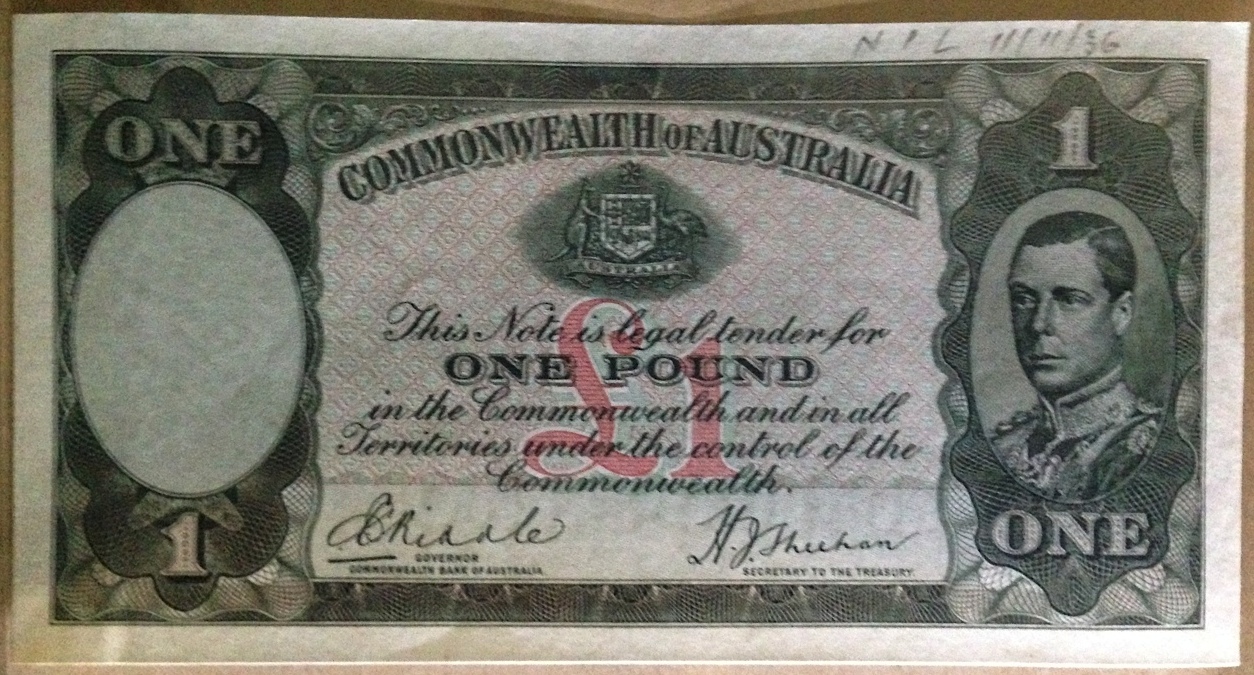

King Edward VIII and Australia’s Notes

Watermarks featuring the portrait of the Prince of Wales were circulating on Australian notes for some 3 years and 3 months before he abdicated the British throne, however no notes featuring his portrait were ever seen in circulation. The reason no notes featuring the portrait of Edward VIII entered circulation in Australia can be put down to the length of time it took the authorities to prepare suitable designs relative to the incredibly short length of Edward VIII’s reign. An unissued specimen note featuring the portrait of Edward VIII on display in the Museum of Australian Currency Notes shows a pencil notation in the top margin of “NPL 11/11/1936”. This date of mid-November 1936 shows that it took 296 days for Australian note authorities to complete a specimen of a currency note featuring Edward VIII, and that King Edward VIII abdicated from the British throne just 30 days after that date.

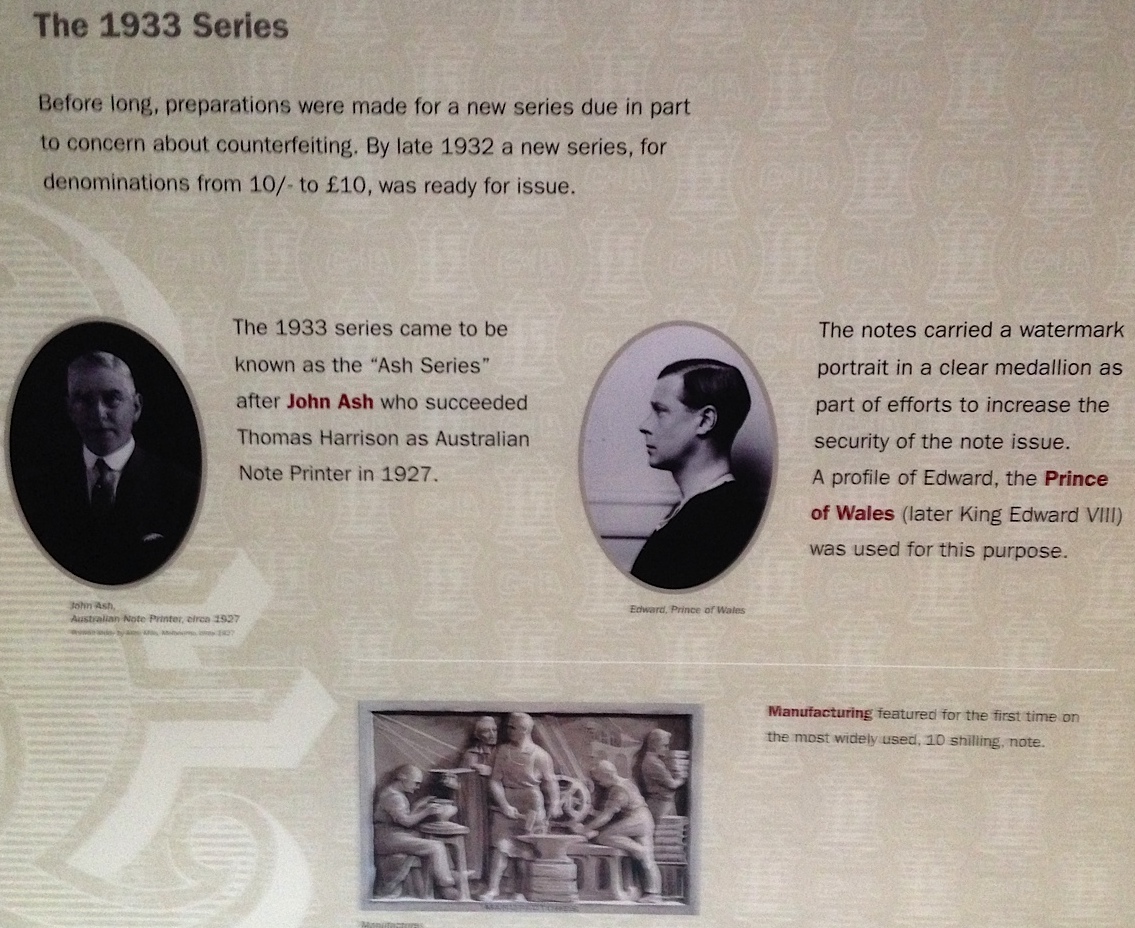

A Comprehensive Review of Australia’s Notes - Legal Tender, Smaller sizes, Stronger Paper and New Watermarks

A comprehensive review of several aspects of Australia’s currency notes was conducted over several stages from the early 1920’s through to the early 1930’s. The most important of these changes was the switch from promising to pay the bearer in gold at the Head Office of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, to stating that the notes were “Legal Tender” throughout the Commonwealth. Rather than there being any concern about the acceptability of the new notes, newspaper reports from the days when the first legal tender ten shilling notes were introduced indicates that at least some members of the general public exchanged their gold-bearing notes for the newer ones so they could be among the first to see them! This switch took place in several stages between July 1933 and October 1934.

The question of an entirely new issue of Australian notes was perhaps first raised at a meeting of the Notes Board on 24 January 1924, but it was apparently not discussed at any length. By May 1928, the Note Printing Board was contemplating a complete new issue of paper currency due to frequent attempted forgeries of the Harrison issues. New designs were then prepared for the 10/- and £1 notes in 1929, but the Government of the day “refused to sanction them.” It felt that adoption of the designs submitted would meet with serious objection, on the grounds that “they did not sufficiently preserve the current Australian character of the notes”. Several of the reports requested by the Note Printer over this decade dealt with the idea of issuing different sized notes for different denominations. Comparison of the sizes of the Harrison series notes with the respective Legal Tender notes that replaced them shows that the £5 and £10 Legal Tender notes were actually 1mm taller and 1mm longer than the Harrison series notes they replaced. The 10/- and £1 notes were reduced in length reasonably significantly by 14%. The 10/- notes were further reduced in length in 1934, to bring them in line with the size of the Bank of England 10/- note, and to ensure that there would be far less possibility of members of the general public confusing it with the £1 note.

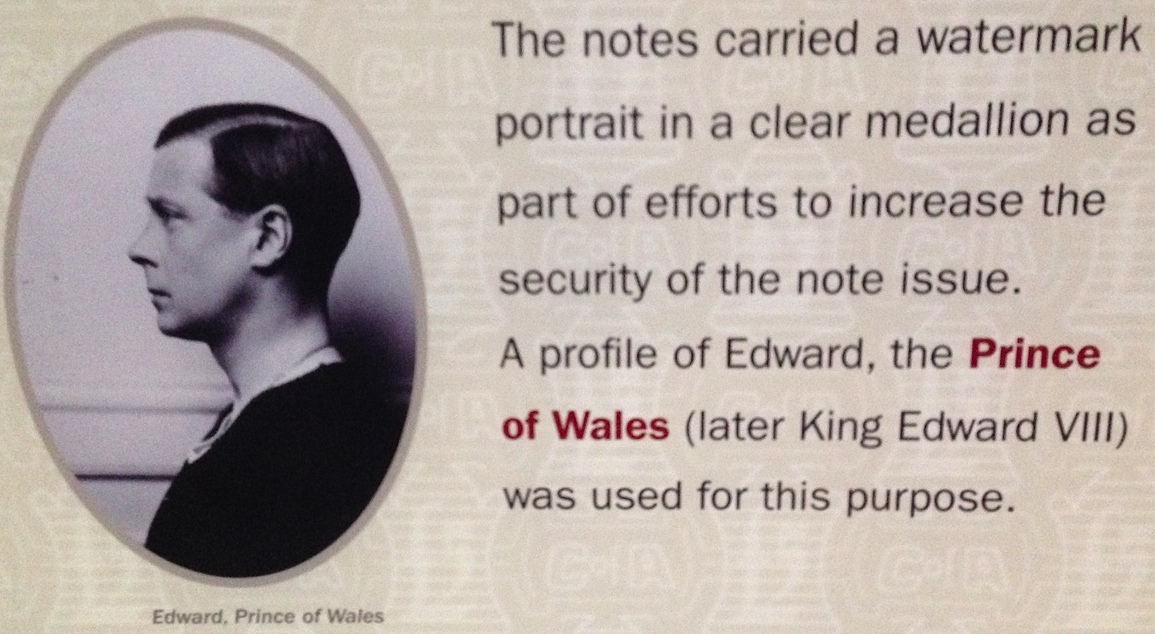

A review of the technical specifications of the paper used for Australia’s circulating currency notes from the early 1920’s through to the early 1930’s shows that while the paper composition remained stable (in terms of the ratio between linen and cotton), the weight of the paper and the strength it was tested to did indeed improve over time. The weight of the paper was increased from 75 gsm to 77 gsm with the introduction of the Legal Tender note series, and the fold number increased from 1,500 to 2,500. Following apparently numerous complaints about the relative flimsiness of the paper used on the newly-introduced legal-tender notes, “long-fibred” paper was introduced from May 1934. The watermarks used on the Harrison series notes were designed specifically to align with the designs of those notes, and as the Legal Tender notes were of a completely different design, a new watermark was of course required. Records of various meetings by the Note Printing Board throughout the 1920’s indicate that the new notes were in fact designed to accommodate a new watermark, one of a portrait in a oval-shaped blank area within the body of the note. The new watermark was to feature a portrait of the Prince Edward, Prince of Wales. Several alternative designs for the watermark were prepared by Portals - Prince Edward personally inspected each of them, and selected one that showed his head in profile to the left. This watermark was first seen by the Australian public each legal tender denomination was issued into circulation between July 1933 and October 1934. Newspaper reports on the day describe the enthusiastic reception the ten shilling note received: ”Many people who were anxious to see the new design changed other notes into 10/- ones. One of the first acts of most of the recipients of the new notes was to hold them up to the light to look through the oval space, or “window,” as it is termed, to see the water-mark profile of the Prince of Wales.” The portrait of Prince Edward was therefore gracing Australia’s currency notes for over three years before his short-lived reign as King took place. Although George VI replaced Edward VIII on as the King of England on 12 December 1936, notes featuring the Prince of Wales watermark were not completely phased out by a watermark featuring a portrait of Captain James Cook until June 1940 - over three years after King Edward VIII’s abdication from the throne.

The Technical specifications of the Blank One Pound Note

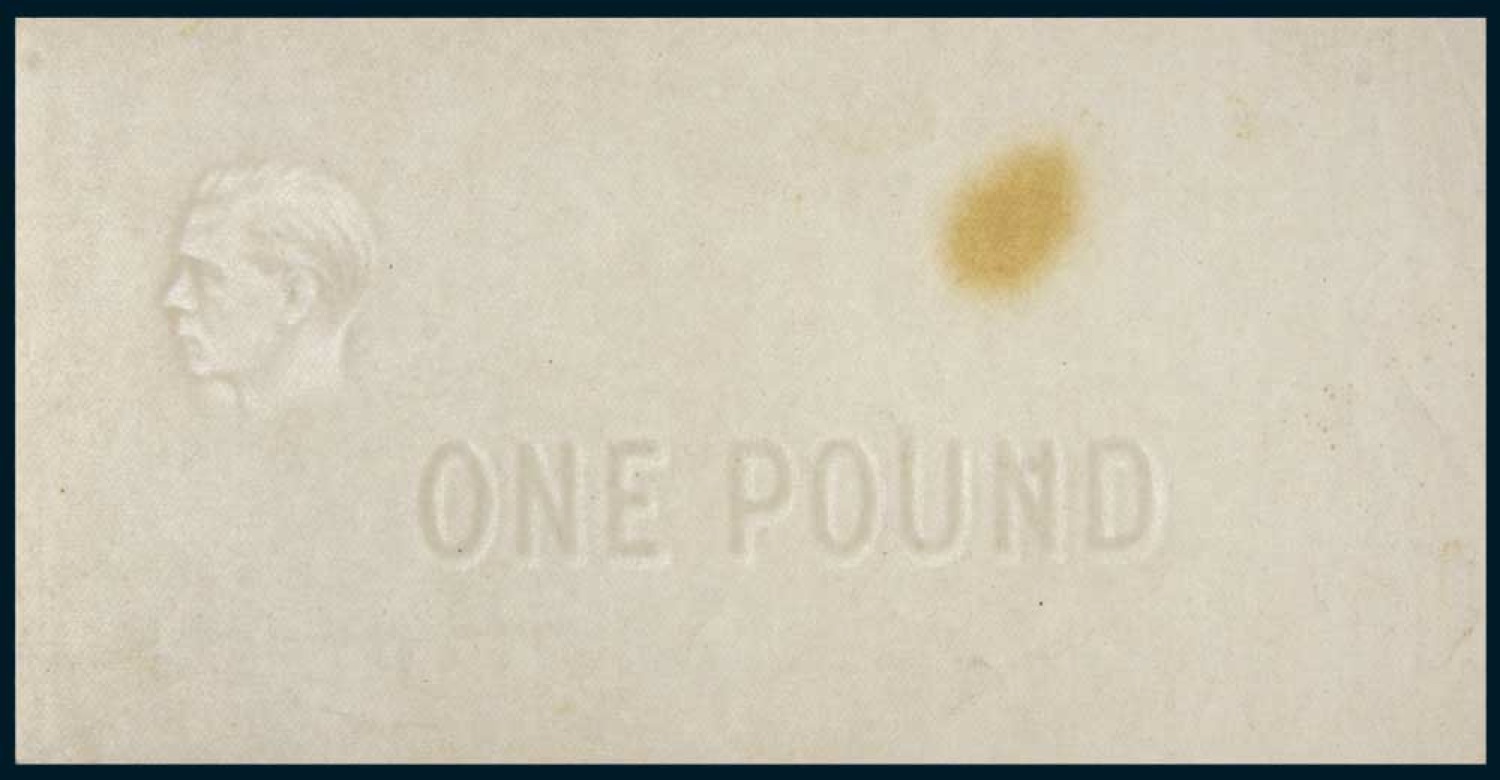

Official measurements for the Australian legal tender one pound notes [R28] are 155mm long * 79mm high, whereas the unissued note form featuring a portrait of Edward VIII in profile to the left as the watermark measures 153mm long * 78mm high. Although the unissued note form is clearly very slightly smaller than the standard note, it is well within reasonable tolerances. The Prince of Wales watermark on the unissued note form is approximately 21mm wide, and approximately 26mm tall. It is placed on the left hand side of the note 16mm in from the left hand edge, and 16mm down from the top edge. The Prince of Wales watermark on an issued Legal Tender one pound note is approximately 23mm wide, and approximately 27mm tall. It is placed on the left hand side of the note 11mm in from the left hand edge, and 29mm down from the top edge. The watermarked notation “ONE POUND” on the unissued note form is approximately 78mm wide, and approximately 14mm tall. It is placed on the left hand side of the note 42mm in from the left hand edge, and 44mm down from the top edge. The watermarked notation “ONE POUND” on an issued one pound note is approximately 63mm wide, and approximately 7mm tall. It is placed on the left hand side of the note 47mm in from the left hand edge, and 61mm down from the top edge.

Although the difference in the placement of the Prince of Wales watermark between the two notes could be easily explained by the manner in which the note form was cut from the sheet it was from, the difference in the size and shape of the lettering in the watermarked notation “ONE POUND” cannot. This significant difference identifies the blank one pound note form as being quite different to the Australian legal tender one pound notes [R28] issued between 24 August 1933 and 22 September 1938. Two of these unissued note forms are known in private hands - the first of these appeared in a Spink Australia auction in November 1980. The auction lot description included the following statement: “This paper was never used for the one pound notes of George VI as intended.” The reference to King George VI appears to have been a typographical error, as the next auction listing for the same note, in a Noble Numismatics auction in July 2009 included the following comment: “This paper was never used for the one pound notes of George V as intended. According to “Australian Banknotes” by Michael P. Vort-Ronald published in 1979, page 93, commencing 24th August 1933, the one pound notes had a watermark of the profile of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) and facing to the left. The profile measured approximately 22mm x 25mm. In addition the words “ONE POUND” appeared in the signature panel. The “ONE POUND” measured approximately 63mm x 7mm. This trial specimen has the profile measuring only 20mm x 22mm, and the “ONE POUND” being larger at 76mm x 14mm. Ex Spink Australia, Sale 4 November 1980, lot 390."

Comparison of the unissued note form with one of the first £1 notes issued under the reign of King George VI, one with the signatures of Sheehan and McFarlane, shows that the watermarks on the two notes are again quite different. For all intents and purposes, the watermark on the Sheehan McFarlane £1 note appears to be same to that on the legal tender one pound notes [R28] issued between 24 August 1933 and 22 September 1938. The definitive work on the coins, medals and banknotes of Edward VIII, “Portraits of a Prince”, by Joseph Giordano Jr., lists the only other currency notes related to Edward VIII issued anywhere in the British Empire was a small series of notes issued in Canada. Each of these notes were denominated in dollars, which precludes Canada as a possible source of this note. While England’s legal tender notes are of a similar size and are from the same era, they are of a completely different design, which precludes England as a possible source of this note. With all of the above information taken into account, it seems that the unissued one pound note forms are an early trial for the paper used for Australia’s legal tender series of notes, and were most likely prepared between 1929 and 1933. As the watermark clearly does not come close to fitting within the signature panels of either the Legal Tender notes, nor the notes of King George VI, it will be interesting to see if the watermark was designed to fit within a larger signature panel for an unissued note that has not yet surfaced on the open market. As of February 2014, no such note has ever been sighted.

Comparative Pre-Decimal and Decimal Notes

The relative value of these notes can be determined by comparing them against other rare pre-decimal and decimal banknotes.

Unissued Specimen Notes [Legal Tender]: The most recent auction appearance of an unissued specimen of a King George V Legal Tender [R28] one pound note was in January 2004: Lot #230, International Auction Galleries Auction 59 (January 2004). Estimate: $85,000, Hammer: $60,000, Nett: $68,250.

Pre-Decimal Error Notes: Pre-decimal error and or variety notes are very seldom seen indeed. The two known unissued Edward VIII one pound note forms are the only blank notes dating to Australia’s pre-decimal period. Paper and Polymer Decimal Error Notes: Up to around 30 different blank polymer notes are known - most of these are polymer $5 notes, far fewer are known of the other polymer denominations. In Australia’s paper decimal notes, there are a number of notes in each denomination that have been printed with the intaglio (black) printing phase missing. A larger number of Australia’s paper decimal notes have been sighted with the simultan (colour) printing phase missing. Depending on condition, denomination, period of issue and error type, paper and polymer decimal note errors such as those listed above generally bring between $1,000 and $3,000 in the current market.

These unissued note forms are literally a unique link to the introduction of the end of the gold standard in Australia, as well as to the controversial and tragic figure of King Edward VIII.