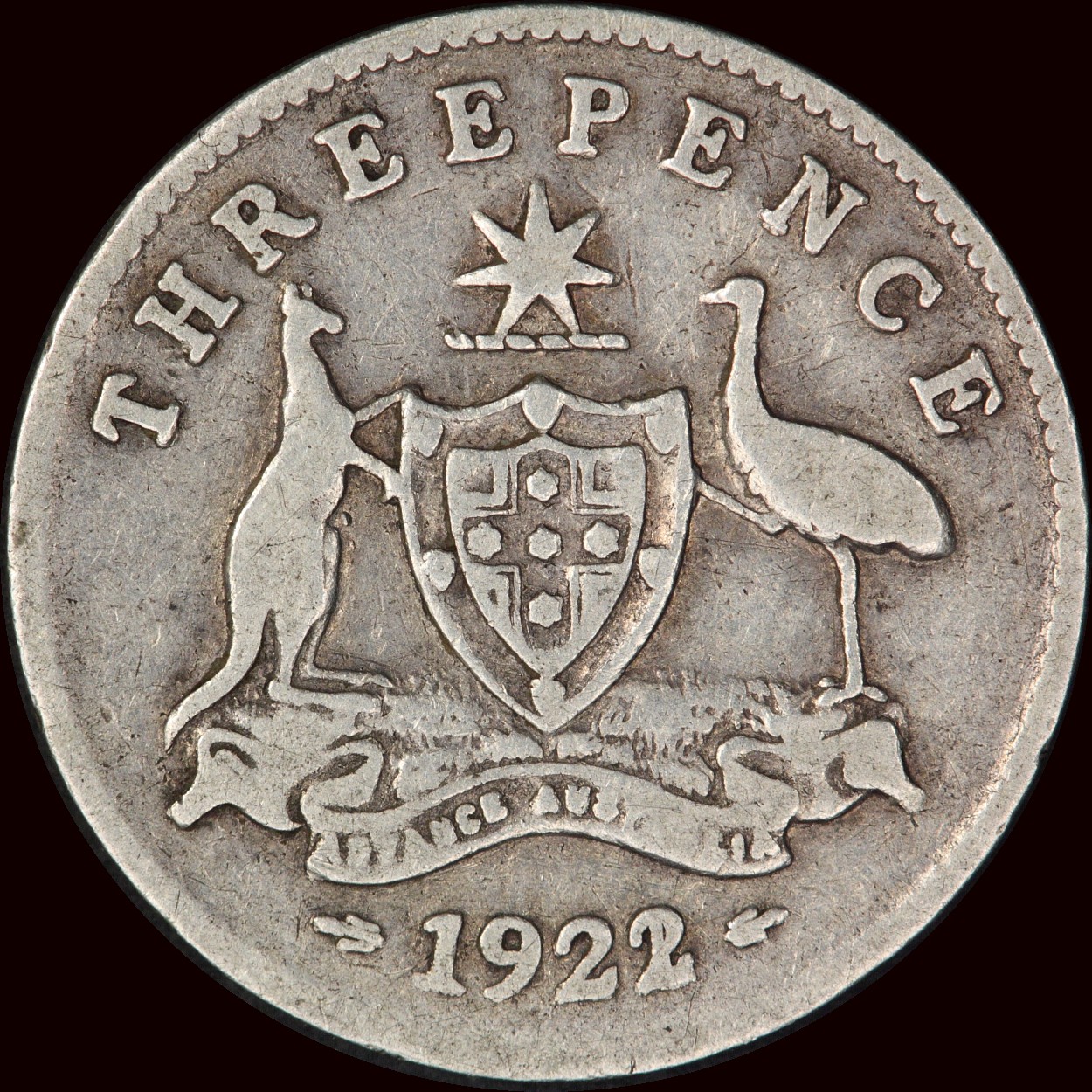

The 1922/1 Overdate Threepence - Australia's Rarest Silver Commonwealth Coin

The 1922/1 overdate 3d is the rarest silver pre-decimal coin issued for use in circulation. To say that there isn't universal agreement about it's background within the Australian numismatic fraternity (past and present) is a mild understatement. In fact, it's been the source of heated debate over the past 40 years or so. Whatever the cause of the anomaly on the date of this coin, it remains one of the most highly prized coins in the entire Australian pre-decimal series.

While the 1930 penny and other rare pre-decimal coins are relatively well known by the general public, the 1922/1 overdate 3d is more of a numismatist's rare coin – understood and appreciated only by those that have been involved in numismatics for some time. Although the first published reference to it dates back to the 1920's, there had been less than 10 examples reported known by the 1970's.

There have been a number of well-researched articles published on this coin over the years:

-

In the Australian Numismatic Journal back in 1961 (reprinted again in the Australian Numismatist in 1988);

-

In the Australian Coin Review in June 1971;

-

In the Australian Coin Review in October 1971; and

-

In the Australian Coin & Banknote Magazine in September 2003.

The best way to learn about the history of this key Australian rarity is to track down and read the above articles, rather than re-hash a lot of the original research that's already been done, I'll cover the story to date in bullet points:

-

The line through the last digit of the date on the 1922/1 3d has always been regarded by collectors as an overdate, ever since it was discovered in the 1920's;

-

In the 6th Annual Report of the RAM (released in 1971), Mr JM Henderson, Controller of the RAM, denied that the vertical line in the last digit of the coin's date was an overdate, and stated that the extra portion of metal was the result of a die spall;

-

This response was strongly disputed by the editorial staff of the ACR, as well as a number of other numismatists;

-

There is still a level of uncertainty regarding the manner in which the overdate was produced.

I thought it was best to get clear on the definition of the term “overdate”, and to also become clear on the standard production process for coins before throwing my own opinions into the mix.

There are numerous definitions of the term overdate available in printed numismatic dictionaries and online – here's my own explanation of what an overdate is:

An overdate is a coin that has one digit in the date with another number (generally from a previous year) visible beneath it. Overdate coins can comprise a small or large portion of a denomination's production run, or can form all of a coin's production run.

Over-dated coins are produced by production-ready dies or hubs being struck with a master die or working hub that has a different date. Here is a quick overreview of the process leading up to a coin being struck:

-

The coin design is selected & approved;

-

A sculptor creates a plaster model of the coin's design. The artist will work from a drawn / sketched or computerized image to produce the plaster mould. Due to the difficulty a sculptor has in working with a small surface area, the plaster model is always significantly larger than the coin's actual size, and must be reduced to actual size.;

-

The plaster model is coated with rubber and / or epoxy to produce a galvano. The rubber mould / epoxy galvano is used because the original plaster design would be badly damaged by the image reduction process. Epoxy is a hard form of plastic that allows for sharp design detail to be transferred.;

-

A Janvier Transfer Reducing Machine is used to reduce the image on the epoxy galvano onto a metal master hub. Once the master hub has been produced, the design is the same size as it will be on the coin itself. In order to ensure that design is transferred accurately, a hub or die will be annealed and re-struck at least twice, if not numerous times before it is finally ready. Dies and hubs are annealed at each step of the process, this ensures that the metal is able to accept the design being struck onto it without being damaged;

-

The metal of the master hub is hardened;

-

A small number of metal master dies are produced using the master hub;

-

These master dies are used to make working hubs;

-

The working hubs are used to make working dies;

-

The working dies are used to strike coins.

Prior to, or at the same time as this process is taking place, the following steps happen:

-

Metals are melted and combined to produce ingots in the alloy required;

-

The ingot is rolled into a sheet;

-

Blank discs (“blanks” or “planchets”) in the correct size are punched from the rolled sheets;

-

The blanks are edged and / or annealed to prepare them for being struck;

-

The working dies are used to strike coins from the annealed blanks.

Some Conclusions

With this knowledge in mind and with access to the research already published on the 1922/1 overdate 3d, I've arrived at the following conclusions:

A simplistic explanation of die spalling is that it is a result of a die or hub face rusting. As the rust progresses to an advanced state, flakes of metal can fall off the face of a die.

This spalling ensures that the appearance of coins that are struck with the spalled die can appear to have a small protrusion of metal “added” to their surface. If the metal flake lands on another section of the die face prior to a coin being struck, the appearance of coins that are struck with the spalled die can appear to have a small chip of metal removed from their surface. The explanation provided by the RAM's Controller in 1971 did not properly explain the spalling process, which led to his explanation being widely ridiculed by collectors.

Perhaps if Mr Henderson had more clearly explained the spalling process, it may have been accepted in a more receptive manner.

Die spalling could conceivably impart an additional design characteristic to a coin's relief, however it is highly unlikely that die spalling explains the 1922/1 overdate. Rust is a natural occurrence - very few natural phenomena occur in a geometric or linear manner, rust certainly isn't among them!

I cannot find one single reference in the world numismatic media to die spalling causing a significant die variety, let alone one as distinctive as this apparent overdate.

The chances of spalling causing the vertical line within the last digit of the date of this coin therefore are inconsequential, and the RAM Controller's explanation in 1971 should be disregarded.

|

Sovereigns |

Half Sovereigns |

Commonwealth Coins |

|

1860 / 50 Type II Sydney Mint |

1859 / 8 Type II Sydney Mint |

1922 /1 3d |

|

1861 / 0 Type II Sydney Mint |

1860 / 5 Type II Sydney Mint |

1925/3 Shilling |

|

1865 / 4 Type II Sydney Mint |

1861 / 0 Type II Sydney Mint |

1933/2 Penny |

|

1872 / 1 Melbourne Shield |

1858 – RR in reverse legend |

1934/3 3d |

|

1879 Sydney Shield – C / O |

|

|

|

1880 Sydney Shield – A / V |

|

|

Further to this list, detailed and consistent study over the past decade of British coins produced during the reign of Queen Victoria by collectors in the UK has yielded no less than 46 distinct date varieties (3 in one year alone!). I might add that this number does not include the number of legend varieties that have been discovered.

These rather extensive (and undoubtedly growing) lists of varieties should be unambiguous evidence that although Royal Mint staff deserve their reputation for excellence, they obviously took short cuts in the die production process on numerous occasions.

There is a die flaw on the reverse of all genuine 1922/1 overdate 3ds that has not yet been raised in the context of this discussion – it is positioned on the reverse in front of the kangaroo's pouch. Many collectors have solely used this planchet characteristic as a test as to whether a potential purchase is genuine or not, and to the best of my knowledge, it hasn't been discussed or studied in any other context.

Die Deterioration

This die flaw may in fact be an indicator of die deterioration, and could be important in determining the manner in which these coins were produced. I would presume (not always a wise idea by any means) that a working die being struck again by a working hub would involve a significant amount of pressure. I would therefore expect that if the die flaw was evident on the original 1921 die, if it was struck by a working hub to add the new last digit to the date, the pressure involved would have surely ensured that the die flaw was effectively erased. Whether this theory is correct or not will be determined by further discussion.

Following his discussion with Melbourne Mint staff in the early 1920's, Ron Stewart stated that the 1922/1 3d is a genuine overdate produced by hand-stamping a 2 onto one of the seven 1921 reverse dies in stock in mid-January 1922, perhaps as an experiment to test the possibility of using some of the newly-pressed but obsolete reverse dies. This has been agreed with by John Saxton.

The rarity of the 1922/1 overdate, as well as the fact that all known examples exhibit the same die flaw, indicates that just one die was involved in their production. This fact precludes the overdate being caused by a master hub being struck a second time, and, as proposed previously, was either the result of a 1921 working die being stuck by a 1922 reverse working hub, or the last digit on a 1921 working die being hand-struck by a “2” date punch. I don't yet know enough about the the manner in which branch Mint staff altered the dates of dies and hubs used for Australian coins during this period to comment whether this was the likely cause or not.

After having interviewed Melbourne Mint staff directly, Ron Stewart clearly states in his 1961 article that there were definite attempts by Melbourne Mint staff to alter the dates on the 3d dies for 1921. What he does not clearly state is just how these date alterations were carried out – the most likely answer will be arrived at with further study and discussion.