The Electrotypes of the 1852 Adelaide Ingot

The 1852 Adelaide Ingots are counted among Australia’s most historic numismatic items - they were the very first items produced by the Adelaide Assay Office following the discovery of gold at Mount Alexander (in Victoria) in November 1851.

These enigmatic slabs of gold are incredibly rare - just 2 exist in private hands anywhere in the world.

According to a noted authority on the Adelaide Assay Office, James Hunt-Deacon, “The introduction of the Bullion Act and the subsequent coinage … was a masterly stroke of legislature, and played no small part in averting economic catastrophe and laying the foundation for a stabilized currency.[1]”

Electrotypes Are Widely Regarded As A Legitimate And Affordable Representation

The only real way most mortal collectors will ever be able to include a representative Adelaide Ingot in their collection is via the ownership of an electrotype - an accurate duplicate of a genuine example, expertly-made by a craftsman experienced in this specialized process, someone with legitimate access to a genuine example held by a public collection.

Electrotypes of the Adelaide Ingot have been made by several different numismatists, most are widely regarded as being a legitimate and affordable representation of the very first numismatic items struck in gold in Australia.

A definitive description of the woeful state of the South Australian economy prior to the introduction of the Bullion Act may be found in a speech made by a member of the South Australian Legislative Assembly in April 1853. George Elder described it as a time “when public and private credit were menaced by imminent and immediate peril – when every man amongst us, however flourishing his previous circumstances and however ample his resources, was threatened with impoverishment, if not with utter ruin – when the honest trader was driven to his wit’s end for the means of meeting his engagements – when general panic and dismay pervaded all classes throughout the colony.”[2]

Just what could have happened to cause such economic distress?

Economic Distress in 1851

Contemporary reports suggest that once the discovery of gold at Mount Alexander became known in Adelaide, over 8,000 men (from a total population of approximately 50,000) decamped to the goldfields. The impact that this gold rush had on those that remained in Adelaide was plain – the main contributors to the local economy simply were not available. “It was with difficulty the harvest was got in. Mining and other productive operations requiring numerous hands were suspended.[3]”

The crippling effects of this labour drain were further compounded by the Adelaide monetary system being bled dry of circulating coinage. Prospective miners obviously needed to support themselves until they found a payable gold strike (an uncertain event at least weeks, if not months away), and as such took as much hard currency to Mount Alexander as they could get their hands on. This made it nigh impossible to conduct even the simplest daily transaction, and business in Adelaide largely ground to a halt. Matters did not improve until some of the men began to return to Adelaide in early January 1852, bringing with them some £50,000 worth of gold. Owing to the scarcity of coinage, merchants and bankers were forced to accept gold nuggets and dust in payment for goods. It did not take them long to petition the colonial government to intervene and establish a mint, an action that would be in direct conflict with the Royal prerogative to issue coinage. A memorial to this effect was put to the Lieutenant Governor on January 9th, 1852.

The gentleman in question was Sir Henry Young, a 41-year-old with legal training and a man who would have clearly understood the precarious position he was placed in. If he permitted the minting of coins he would in effect contravene the Royal prerogative, while if he disallowed them he would undoubtedly earn the ire of Adelaide’s merchants & bankers. Not only would approval be required from London before any such planning could be brought to fruition, but legislation would also have to be passed. This potential delay was obviously exacerbated by the time taken to travel between London and Adelaide, around 90 days in itself. Each of these factors would have weighed heavily on Young’s mind, particularly since the fledgling colony was at that time gripped by economic depression and drought.

As he did not have the benefit of consulting his superiors in London for advice within a timely period, Young spent some time discussing the matter with the prominent bankers of the day. Mr George Tinline, acting manager of the South Australian Banking Company, was whole-hearted in his support for the idea, while the other two banks that were represented were either negative or lukewarm. Despite Tinline’s determined petitioning, Sir Henry Young declined the proposal for a mint to be established, stating it to be “either impracticable, ineffectual or imperfect.[4]”

Not to take such a setback as the final word on the matter, the merchant community submitted a second proposal four days later. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that as committed as Sir Henry Young was to supporting economic development in Adelaide, he could only do so legally if a way through the legislation governing the colony could be found. Instructions to governors of British colonies on the matter of currency were very clear – they were “prohibited assenting in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony,[5]” and it was this point that prevented Young from allowing a mint to be established. Fortunately, a proviso to this directive was included, and stated, “unless urgent necessity exists requiring that such be brought into immediate operation.[6]”

It was this proviso that provided Young with the means by which he could balance both the needs of the colony and his legal responsibilities. The Executive Council of the colonial government met on January 22nd to discuss the issue further, at this meeting it was proposed that the raw gold arriving in the colony could be converted into a form that would benefit the economy without coins needing to be produced.

A Legal and Practical Solution - Brought Into Law Within 2 Hours

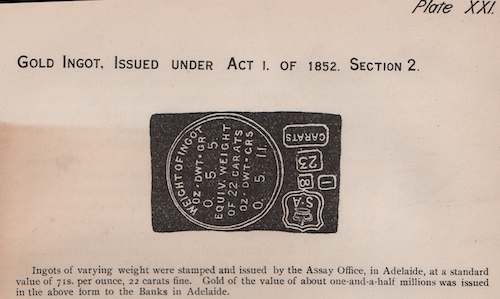

The following solution was reached: raw gold could be taken to an assay office, where it would be refined and made into ingots, then stamped to indicate their weight and purity. These ingots could then be taken to one of the banks and offered as security against an issue of currency notes to the value of the gold. It was reasoned that business would be facilitated through the availability of these currency notes, and the royal prerogative on the issue of currency would remain unviolated.

Sir Henry Young sought advice from his Treasurer; the Advocate General; the Crown Solicitor and two judges, and all were of the opinion that the solution would be acceptable to London. “A Bill to Provide for the Assay of Uncoined Gold and to Make Banknotes, Under Certain Conditions, A Legal Tender” was proposed to the Legislative Council on January 28th, and became law as the Bullion Act within a staggering two hours.

The Adelaide Assay Office was opened on February 10th, and on the first day of operations gold to the value of £10,000 was deposited.

Of the many Adelaide Ingots that were produced between March 4th 1852 and late September 1852, just eight remain in existence. Six of the Adelaide Ingots are in public collections around the world, and the only two in private hands held pride of place in the Quartermaster collection – easily the finest collection of Australian gold coins ever formed.

The excessively rare Adelaide Ingots are rightly regarded as being integral to the history of Australian numismatics, and are highly coveted by collectors the world over.

Adelaide Ingot Type I - Cast In An Irregular Shape

Despite the wealth that the Bullion Act brought to the colony, the ingots were criticised for their lack of uniformity – due to the variation in deposits made to the Assay Office, each ingot was unique in shape, colour and purity. Conventional economic theory states that money has several basic characteristics – durability, portability, divisibility, and convenience are among them . The fact that the Ingots were neither divisible nor convenient meant that they were destined to be short-lived.

Although the Colonial Treasurer intended that the ingots produced by the Assay Office were to be “ingots of one ounce, or some other convenient weight“[7], the Adelaide Ingots produced initially (Type I) were each cast in an irregular shape – the size and shape were determined primarily by the amount of gold presented by the miner for assay. Markings as to weight and purity are evident on both sides – just three ingots of this type remain in existence.

Adelaide Ingot Type II - Rolled Flat and Trimmed

On January 23rd 1852, a Mr George Francis (the Assay Office Assayer) notified Lieutenant Governor Young that it would not be possible to produce ingots of a uniform standard by casting, and that the only method by which this could be achieved was by rolling or laminating the metal . Accordingly, the second type of ingot was produced in a completely different style – the metal is much thinner than that of the Type I, and each of the five in existence has been rolled flat. Both types of ingot show evidence of having been trimmed, presumably to adjust their weight.

Pressure from the public and the banks resulted in the Bullion Act being amended on November 23rd 1852, to allow the issue of gold coins (although technically they were actually tokens) valued at £5; £2; £1 and 10/-.

Although it is plain that some effort had been made to bring the ingots to some level of uniformity, the prevailing thought was that legal tender pieces in the shape of a coin, and of a uniform weight and purity would ease the difficulties being experienced in using the ingots.

Despite an official concern that the production of the Adelaide Pounds would be seen by London as a violation of the Royal prerogative to issue coinage, daily business in Adelaide was further expedited by their introduction.

The Adelaide Ingots then were sporadically produced after the Bullion Act was established in March 1852, and were superseded by the more uniform Adelaide Pounds from September 1852.

Electrotyping - Using Chemicals and Electricity to Produce Legitimate Duplicates

An “electrotype” coin is a reproduction made by a process combining chemicals and electricity.

Although electrotypes are not original coins, they are not regarded in the same class as counterfeits, forgeries or replicas.

The electrotype process has been used by collectors around the world ever since the process was first invented in 1838,[8] to create examples of rare and historic coins that were otherwise unobtainable.

Not only are electrotypes used to complete a set or collection that would otherwise have a glaring omission, they are also used for study purposes. Experienced collectors of ancient coins have been known to include an electrotype in their collection in order to completely tell the story of the coinage of a particular region or era. Museums have been known to include an electrotype in a display for the same reason, or to minimise the risk of loss in the event of vandalism or theft.

Several Prominent Public Collections Include Electrotypes

Several public prominent collections of Australian coins include electrotypes of Adelaide Ingots - the State Library of NSW (the Dixson collection); Museum Victoria, and the Art Gallery of South Australia are among them.

The State Library of NSW does not have a publicly available image of the original Adelaide Ingots that it contains within the Dixson collection. It does however have two images of an electrotype of the Sawtell / Reynolds / Thomas ingot that it has had since 1912. This particular electrotype is unusual, in that it remains in it’s early “shell” format, and hasn’t had the interior of the shell filled with base metal to more closely resemble a complete ingot.

Although electrotype duplicates are nowhere near as rare as the original ingots, they are still a scarce and desirable collectible that allows a collector to display the story of the early days at the Adelaide Assay Office. Several numismatists have created legitimate electrotype duplicates of Adelaide Ingots over the years - most are attributed to Edwin Sawtell and George Wilkins, while a small number remain unattributed. This is what is known about the two main producers of electrotypes:

Edwin Sawtell - Chronometer and Nautical Instrument Maker

Sawtell was a highly respected “chronometer and nautical instrument maker” that had several businesses at various locations in Adelaide between 1853 and 1889.[11] While James Hunt-Deacon describes Sawtell as being “…a working jeweller of Adelaide[12]”, Sawtell’s obituary and other biographical notes describe him as being “…the oldest watchmaker and optician in Adelaide.[13]” Just prior to his death, his business was described as being “…always a delight to those of a scientific turn, as it abounds in novelties, and the proprietor is still as enthusiastic as ever in the scientific branch of his business.[14]” Sawtell did not appear to have any formal relationship with the Art Gallery of South Australia, Loyau states that “In public matters he took no prominent part, being content to advance the public weal by keeping pace with the colony’s requirements in his special line of business.[15]” Edwin Sawtell died in October 1889,[16] his eldest son Alfred Edwin Sawtell died in 1902,[17] while his second son Charles Sawtell died in 1936.

Hunt-Deacon states that Sawtell owned an Adelaide Ingot now in the Dixson Collection (part of the State Library of New South Wales), together with Thomas Reynolds and Thomas Walters.

The Honourable Thomas Reynolds had a range of occupations throughout his working life: he was variously a congregationalist lay leader, goldminer, grocer, jam manufacturer, local government councillor, Member of Lower House, Member of Upper House, Premier and a temperance advocate.[18]

Thomas Walters is described as being the first headmaster of the first primary school in Adelaide[19] (Crafers Public School).

Just what the relationship was between these three men is not clear, however given their respective occupations, it is not difficult to appreciate that they came together to preserve a unique item of South Australia’s heritage by each taking a share in owning an Adelaide Ingot. With his technical expertise, it is not inconceivable at all that Sawtell either made the electrotypes himself, or commissioned them to his own specifications.

Sawtell’s electrotypes are extremely accurate duplicates, made within 40 years of the ingots being in circulation, by a man that actually owned the ingot being duplicated. They are readily identified by the name “SAWTELL” being punched into one corner of the electrotype, and remain prized by collectors to this day for their rarity and historical importance.

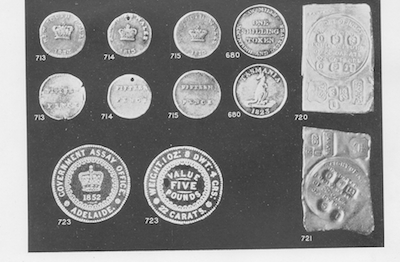

Dr Arthur Andrews includes an electrotype Adelaide Ingot by Sawtell as item 720 in his book “Australasian Tokens and Coins”[20], and describes it as being “very rare”.

James Hunt-Deacon lists several electrotypes in his book "The Ingots and Assay Office Pieces of South Australia”, and regards an electrotype Adelaide Ingot by Sawtell as item 7b in his catalogue.

If Hunt-Deacon is correct in naming Edwin Sawtell as a joint owner of the Type 7 Adelaide Ingot, we can conclude that the electrotypes of that ingot with his surname punched into it, were produced prior to his death in 1889. As Sir William Dixson did not acquire the Ingot until 1912, there is a distinct possibility that the electrotypes were produced by either Alfred Edwin Sawtell, or Charles Sawtell.

George Wilkins - "Colourful" Sydney Coin Dealer

George Wilkins has been described to me by a few old hands in the Australian numismatic trade variously as a coin collector, a coin dealer, a restaurateur, and video store owner.

Wilkins apparently operated a number of coin dealing businesses in various locations throughout Sydney and Wollongong from the mid 1960’s, possibly through to the early 1970’s. I’ve been advised that Mr Wilkins was thought by some to have overstayed his welcome in the Australian numismatic trade, that he may or may not have had some association with Mr David Gee, and that he was

regarded as being one of the more “colourful” dealers that were active when coin collecting was at it’s peak in the mid–1960’s. The electrotypes of the Adelaide Ingot made by Wilkins are readily identified - they feature a small “GW” within a circle, punched into one corner on the front of the electrotype.

These electrotypes are believed to have been produced by Wilkins in the late 1960’s.

The genuine ingot that Wilkins duplicated was a Hunt-Deacon Type 7, Andrews # 720. As this item has been held by the State Library of NSW in the Dixson collection since 1912, Wilkins either had direct access to items in the Dixson collection, illicit access to the Dixson collection, or produced his electrotypes from an existing electrotype, as produced by Sawtell.

Wilkins’ electrotypes are somewhat softer in the detail visible across the obverse. Comparing one with the level of detail on an electrotype produced by Sawtell, we can see that sections of the legend are missing in certain areas. The fact that Wilkins produced his electrotypes uniface and in a base metal, and further as he stamped his initials in one corner, indicates no matter how “colourful” his other business activities may have been, it doesn’t appear that he created them in an obvious attempt to defraud. While they may not have the same gravitas as the electrotypes produced by Sawtell in the late 1800’s, the Wilkins electrotypes don’t appear to have suffered in terms of value when they’ve appeared for sale via auction.

I understand that Wilkins also produced quite acceptable electrotypes of the reverse of a 1930 penny, these are also seldom seen.

Electrotypes of the Adelaide Ingots via Auction

Electrotypes of the Adelaide Ingots have been seen at numismatic auctions since at least 1973. In March of that year, Geoff K Gray auctioneers sold the collection of Gilbert Heyde, former President of the Australian Numismatic Society. Heyde owned two different Adelaide Ingot electrotypes - one a Hunt-Deacon Type 7b (as produced by Sawtell), the second a Hunt-Deacon Type 8.

Both of these items made $310 - equivalent to several Kookaburra pattern pennies, and more than a complete set of 1938 proof coins.

In more recent years, Adelaide Ingot electrotypes have sold for up to $6,000 via auction.

The highest price achieved through auction so far for an Adelaide Ingot electrotype was:

Lot #542, International Auction Galleries Auction 78 (October 2013). Estimate: $3,000, Hammer: $4,950, Nett: $5,903.

Each of the Adelaide Ingot electrotypes that are available to collectors today has a unique appeal, depending on the original ingot it was duplicated from, and depending on the producer of the electrotype.

They all remain an affordable and accurate representation of one of Australia’s rarest, and most historic numismatic items.

- Hunt-Deacon; James, “The Ingots and Assay Office Pieces of South Australia”, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, , p iii. ↩

- Thomas Gill, Coinage and Currency of South Australia, Adelaide: Vardon & Sons, 1912, p50. ↩

- Sir Robert Torrens; (Observations Upon The Working, Present Effects, And Future Tendencies of Act No 1, of 1852, “Making Banknotes Under Certain Circumstances a Legal Tender.”) [Pamphlet printed by the Adelaide Observer, 1852.] ↩

- James Hunt Deacon, The Ingots and Assay Office Pieces of South Australia, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, p9 ↩

- Tom Hanley and Bill James, Collecting Australian Coins, Sydney: Kenmure Press, 1967, p46 ↩

- Tom Hanley and Bill James, Collecting Australian Coins, Sydney: Kenmure Press, 1967, p46 ↩

- Deacon, p12 ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrotyping ↩

- Hunt-Deacon; James, “The Ingots and Assay Office Pieces of South Australia”, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, , p 53. ↩

- B. Cook, ‘Dixson, Sir William (1870–1952)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 23 September 2014. ↩

- Loyau; George, “Notable South Australians”, Carey Page & Co, Adelaide, 1885, p 263. ↩

- Hunt-Deacon; James, “The Ingots and Assay Office Pieces of South Australia”, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, p 53. ↩

- Loyau; George, “Notable South Australians”, Carey Page & Co, Adelaide, 1885, p 223. ↩

- Loyau; George, “Notable South Australians”, Carey Page & Co, Adelaide, 1885, p 223. ↩

- Loyau; George, “Notable South Australians”, Carey Page & Co, Adelaide, 1885, p 223. ↩

- https://histfam.familysearch.org//getperson.php?personID=I42663&tree=SouthAustralia (closed)

- DEATH OF MR. A. E. SAWTELL. (1902, September 3). The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1931), p. 6. Retrieved September 24, 2014, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4875220 ↩

- Gordon D. Combe, ‘Reynolds, Thomas (1818–1875)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 23 September 2014. ↩

- Ancestry.com background information ↩

- Andrews, Dr Arthur, “Australasian Tokens and Coins", Gullick, Sydney, 1921, p 122. ↩