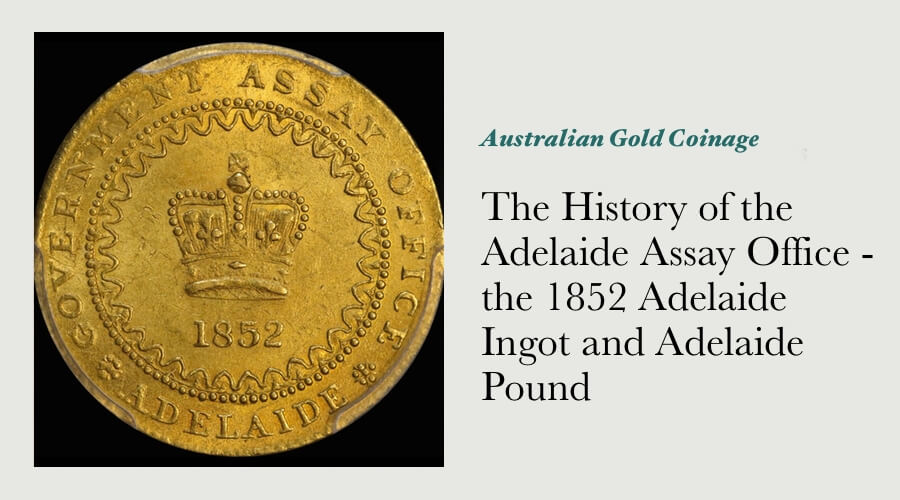

The History of the Adelaide Assay Office - the 1852 Adelaide Ingot and Adelaide Pound

The 1852 Adelaide Pound is Australia’s first gold coin, minted in response to problems caused by the discovery of gold at Mount Alexander (Victoria) in November 1851.

It is one of Australia’s rarest and most coveted coins, and is seldom seen on the collector market. The story surrounding its conception, production and withdrawal has several threads that have been shown to have enduring appeal – the perseverance and foresight of George Tinline; the leadership of Sir Henry Young; the ingenuity of the Assay Office staff and the enterprise of all those that flocked to the goldfields are all stories that strike a chord with Australians in the 21st century.

Imminent and Immediate Peril

A definitive description of the woeful state of the South Australian economy prior to the introduction of the Bullion Act may be found in a speech made by a member of the South Australian Legislative Assembly in April 1853. George Elder described it as a time “when public and private credit were menaced by imminent and immediate peril – when every man amongst us, however flourishing his previous circumstances and however ample his resources, was threatened with impoverishment, if not with utter ruin – when the honest trader was driven to his wit’s end for the means of meeting his engagements – when general panic and dismay pervaded all classes throughout the colony.”

Just what could have happened to cause such economic distress? Contemporary reports suggest that once the discovery of gold at Mount Alexander became known in Adelaide, over 8,000 men (from a total population of approximately 50,000) decamped to the goldfields. The impact that this gold rush had on those that remained in Adelaide was plain – the main contributors to the local economy simply were not available. “It was with difficulty the harvest was got in. Mining and other productive operations requiring numerous hands were suspended.”

The crippling effects of this labour drain were further compounded by the Adelaide monetary system being bled dry of circulating coinage. Prospective miners obviously needed to support themselves until they found a payable gold strike (an uncertain event at least weeks, if not months away), and as such took as much hard currency to Mount Alexander as they could get their hands on. This made it nigh impossible to conduct even the simplest daily transaction, and business in Adelaide largely ground to a halt. Matters did not improve until some of the men began to return to Adelaide in early January 1852, bringing with them some £50,000 worth of gold.

Scarcity of Coinage

Owing to the scarcity of coinage, merchants and bankers were forced to accept gold nuggets and dust in payment for goods. It did not take them long to petition the colonial government to intervene and establish a mint, an action that would be in direct conflict with the Royal prerogative to issue coinage. A memorial to this effect was put to the Lieutenant Governor on January 9th, 1852. The gentleman in question was Sir Henry Young, a 41-year-old with legal training and a man who would have clearly understood the precarious position he was placed in. If he permitted the minting of coins he would in effect contravene the Royal prerogative, while if he disallowed them he would undoubtedly earn the ire of Adelaide’s merchants & bankers. Not only would approval be required from London before any such planning could be brought to fruition, but legislation would also have to be passed. This potential delay was obviously exacerbated by the time taken to travel between London and Adelaide, around 90 days in itself. Each of these factors would have weighed heavily on Young’s mind, particularly since the fledgling colony was at that time gripped by economic depression and drought.

As he did not have the benefit of consulting his superiors in London for advice within a timely period, Young spent some time discussing the matter with the prominent bankers of the day. Mr George Tinline, acting manager of the South Australian Banking Company, was whole hearted in his support for the idea, while the other two banks that were represented were either negative or lukewarm. Despite Tinline’s determined petitioning, Sir Henry Young declined the proposal for a mint to be established, stating it to be “either impracticable, ineffectual or imperfect.” Not to take such a setback as the final word on the matter, the merchant community submitted a second proposal four days later.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that as committed as Sir Henry Young was to supporting economic development in Adelaide, he could only do so legally if a way through the legislation governing the colony could be found. Instructions to governors of British colonies on the matter of currency were very clear – they were “prohibited assenting in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony,” and it was this point that prevented Young from allowing a mint to be established. Fortunately, a proviso to this directive was included, and stated, “unless urgent necessity exists requiring that such be brought into immediate operation.” It was this proviso that provided Young with the means by which he could balance both the needs of the colony and his legal responsibilities. The Executive Council of the colonial government met on January 22nd to discuss the issue further, at this meeting it was proposed that the raw gold arriving in the colony could be converted into a form that would benefit the economy without coins needing to be produced.

The following solution was reached: raw gold could be taken to an assay office, where it would be refined and made into ingots, then stamped to indicate their weight and purity. These ingots could then be taken to one of the banks and offered as security against an issue of currency notes to the value of the gold. It was reasoned that business would be facilitated through the availability of these currency notes, and the royal prerogative on the issue of currency would remain unviolated. Sir Henry Young sought advice from his Treasurer; the Advocate General; the Crown Solicitor and two judges, and all were of the opinion that the solution would be acceptable to London.

A Bill to Provide for the Assay of Uncoined Gold and to Make Banknotes

“A Bill to Provide for the Assay of Uncoined Gold and to Make Banknotes, Under Certain Conditions, A Legal Tender” was proposed to the Legislative Council on January 28th, and became law as the Bullion Act within a staggering two hours. The Adelaide Assay Office was opened on February 10th, and on the first day of operations gold to the value of £10,000 was deposited. In his speech to the South Australian Legislative Council in July 1853, Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Young stated, “the scheme surpassed the expectations of the most sanguine, and completely vindicated the prudence and sagacity of its promoters.” Young pointed towards two facts as being indicative of the success of the Bullion Act. The increased numbers of South Australians returning from the goldfields indicated a collective confidence in the rejuvenated Adelaide economy, while the “accelerated and augmented” sales of Crown land in South Australia was taken to be a demonstration that the newfound economic health was to surely prevail for years to come.

Of the many Adelaide Ingots that were produced between March 4th 1852 and late 1852, just eight remain in existence.

Six of the Adelaide Ingots are in public collections around the world, and the only two in private hands hold pride of place in the Quartermaster collection – easily the finest collection of Australian gold coins ever formed. The excessively rare Adelaide Ingots are rightly regarded as being integral to the history of Australian numismatics, and are highly coveted by collectors the nation over.

Despite the wealth that the Bullion Act brought to the colony, the ingots were criticised for their lack of uniformity – due to the variation in deposits made to the Assay Office, each ingot was unique in shape, colour and purity. Conventional economic theory states that money has several basic characteristics – durability, portability, divisibility, and convenience are among them. The fact that the Ingots were neither divisible nor convenient meant that they were destined to be short-lived.

Not only were the ingots not conducive to circulating as money, but also the banks felt quite restricted in their obligations to holding them. Recent numismatic research on the methods by which the Ingots were produced shows that the Assay Office staff were not only aware of these concerns, but actually took measures to alleviate them. The eight Ingots that remain in existence are differentiated by numismatist into two distinct categories – Type I and Type II.

Cast In An Irregular Shape

Although the Colonial Treasurer intended that the ingots produced by the Assay Office were to be “ingots of one ounce, or some other convenient weight," the Adelaide Ingots produced initially (Type I) were each cast in an irregular shape – the size and shape were determined primarily by the amount of gold presented by the miner for assay. Markings as to weight and purity are evident on both sides – just three ingots of this type remain in existence.

On January 23rd 1852, a Mr George Francis (the Assay Office Assayer) notified Lieutenant Governor Young that it would not be possible to produce ingots of a uniform standard by casting, and that the only method by which this could be achieved was by rolling or laminating the metal. Accordingly, the second type of ingot was produced in a completely different style – the metal is much thinner than that of the Type I, and each of the five in existence has been rolled flat. Both types of ingot show evidence of having been trimmed, presumably to adjust their weight.

Pressure from the public and the banks resulted in the Bullion Act being amended on November 23rd 1852, to allow the issue of gold coins (although technically they were actually tokens) valued at £5; £2; £1 and 10/-. Although it is plain that some effort had been made to bring the ingots to some level of uniformity, the prevailing thought was that legal tender pieces in the shape of a coin, and of a uniform weight and purity would ease the difficulties being experienced in using the ingots. Despite an official concern that the production of the Adelaide Pounds would be seen by London as a violation of the Royal prerogative to issue coinage, daily business in Adelaide was further expedited by their introduction.

Interestingly, the “fine” weight (the actual gold weight once impurities have been taken into account) of the Type II ingots (those produced toward the end of 1852) comes quite close to that of the Adelaide Pound. The main conclusion that may be drawn from this progression towards uniformity in the Assay Office’s issue is that a clear attempt was made to increase the convenience associated with the use of the ingots - to increase their acceptability and perhaps to reduce the inconvenience being felt by the banks. Once analysis of this theory is taken to a deeper level of detail, the story of the Adelaide Assay Office’s Ingots and Pounds will provide an intriguing economic case study in the evolution of money in Australia.

Only 4 Adelaide Pounds Were Actually Issued in 1852

One interesting observation of official records is that only four Adelaide Pounds were actually issued in 1852, and that just 24,648 Adelaide Pounds were ever struck - the last produced on February 13th, 1853. The £1 token was the only size produced – although dies were prepared for the £5, neither this size nor the £2 or 10/- sizes were struck for circulation.

Although none of the £5 pieces were ever struck for circulation, twelve examples were struck at the Melbourne Mint (using the official dies) in 1921. Due to a lack of demand from the collector market, five pieces were melted down in 1929, while another five remain in public collections in Australia and around the world. Just two examples of the Adelaide Assay Office Five Pound are available to the collector market, making them one of Australia’s rarest and most historic coins.

London’s Reaction to the Bullion Act

London’s first official reaction to the Bullion Act arrived in Adelaide (via Despatch # 65) in May 1853 , and was overwhelmingly positive – Lieutenant Governor Young was congratulated for the manner in which he had met a crisis of “peculiar urgency and danger.” This correspondence included a presumption that Adelaide’s currency crisis had since been resolved by the export of large amounts of British coinage, indicating perhaps that London did not fully understand the extent of the problems the South Australians were facing.

When news of the second round of legislative amendments (permitting the production of the legal tender Adelaide Pounds) finally reached London in January 1853 (via Despatch # 85), Young was directed to repeal either the whole Bullion Act or at least parts of it. Ironically, this directive did not arrive in Adelaide until August of 1853 , yet the Bullion Act had already been revoked several months earlier. Clause 4 of the Bullion Act stated that if the amount of gold deposited at the Assay Office within one calendar month was less than 4,000 troy ounces, the Lieutenant Governor had the power to revoke the Act and close the Assay Office. Aware that his bold decision in assenting to the Bullion Act had more than achieved the aim of reviving the South Australian economy, and that the supply of labour & currency had improved markedly, Young readily cancelled the historic Bullion Act on February 3rd, 1853.

When the very first Adelaide Pound was struck on September 23rd 1852, Adelaide Assay Office staff became aware of a significant problem – a small crack had appeared between the inner circle and the outer rim at the top of the reverse die (Type I). This indicated that the pressure being used was too great - the Assay Office staff took several measures to alleviate the problem. The first step was to obviously produce another reverse die (Type II), while the second was to produce another edge collar; this one with slightly wider edge milling (Type 1b).

While the Type II reverse die was being designed and engraved, several more coins were struck with the first set of dies to test the new edge collar. Die pressure was reduced on both sides, the resulting examples being observed for any further deterioration of the reverse die. The new (second or Type II) reverse die would not have been put into use until the Assay Office was confident that the new edge collar solved the problem. Numismatic research of the Type 1b (wide edge) Adelaide Pounds confirms that the die pressure was indeed reduced for examples struck with the wider milled edge – this is particularly evident in the crown of the obverse, as well as near the “N” of “ONE” on the reverse.

The exact number of Type I Adelaide Pounds (including both A and B varieties) struck is not known, although contemporary reports suggest that between 25 and 30 examples of this excessively rare Australian coin were produced.

Interestingly for such a historically important and rare Australian coin, a good number of the Type I Adelaide Pounds that remain in existence have been mounted in a piece of jewellery, exhibit planchet flaws, have contact marks to some degree or are heavily worn. Conservatively, less than ten examples of the Type I Adelaide Pound remain in existence in Extremely Fine quality or better. Several of the finest Australian coin collections ever formed (the Marcus Clarke & H.C Dangar collections for example) included Type I’s of this grade, while several other major collections (including Gilbert Heyde’s) included lower quality coins.

Solid Testament to Australian Ingenuity

The Adelaide Ingots and Pounds remain to this day as solid testament to Australian ingenuity during a period of social and economic turmoil. From an economic perspective, research into the gradual move from gold nuggets and dust being exchanged for goods to the return of sovereigns in daily trade is a unique and intriguing case study of the evolution of money in an Australian context. The appeal of these national heirlooms to historians and collectors is heightened further when their rarity and fragile beauty in superior quality is considered. Very few collectors ever enjoy the opportunity of owning either an Adelaide Ingot or Pound, and it is hardly surprising that they are keenly sought by collectors the nation over.