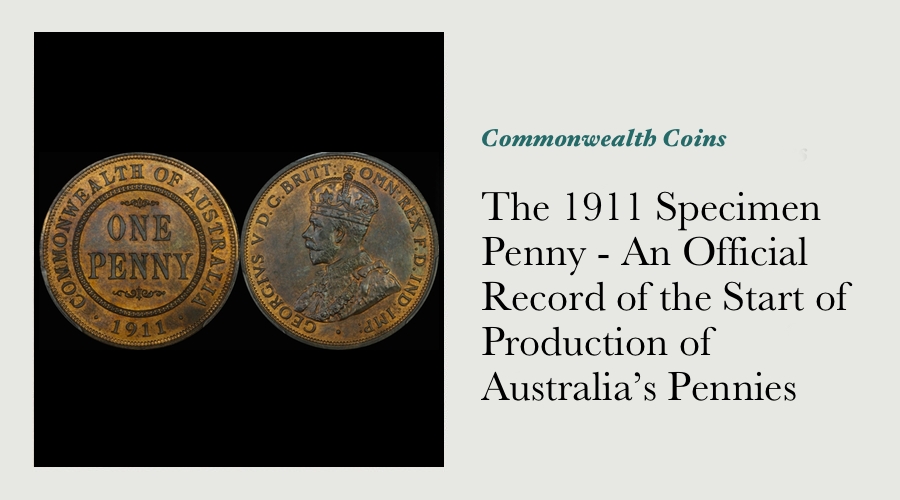

The 1911 Specimen Penny - An Official Record of the Start of Production of Australia’s Pennies

The 1911 Specimen Penny

Although this incredibly important Australian coin has appeared at auction twice in the past 18 months, in my opinion collectors don’t yet fully appreciate just how historically important and rare it is.

This coin is in fact an archival-standard strike of Australia’s very first penny - it is one of only 2 known in private hands, and was struck for the express purpose of officially recording the start of the production of Australia’s first Commonwealth pennies.

It is important for a number of reasons - not only is it one the very first Australian pennies ever struck, it also showed for the first time the most acclaimed work of one of Australia’s most celebrated sculptors, at a time when Australian talent was just emerging on the world stage. Finally, it features the portrait of the monarch that was seen by the Australian public as being their “Royal Champion of the Colonies”.[1]

The Most Collected of All Australian Coins

The penny is easily the most collected of all Australian coins - more pennies were struck than any of the other Australian pre-decimal denominations, they hold a sentimental place in the heart of everyone that lived in the days before dollars and cents.

When we consider that more than 742 million Australian pennies were produced between 1911 and 1964, the opportunity to own one of the coins intended to record the start of that production run is surely incredible.

A Royal Comrade of Australians

Although Australians have warmly regarded each British monarch that has reigned since King George III, King George V seems to have held a special place among them.

A young Prince George first visited Australia when he was just 15, while serving with his older brother Albert as midshipmen on a Royal Navy vessel that patrolled the sea lanes of the British Empire. While on his journey home from Australia in 1881, Prince George wrote in his personal diary:

“After England, Australia will always occupy the warmest corner of our hearts.[2]”

When extracts from the young prince’s diary were published in 1902, it inspired a groundswell of affection and loyalty in Australia.

Prince George next visited Australia in 1901, when he opened Parliament House in Canberra. Once he returned to Britain, a speech Prince George gave in London again voiced his support for the colonies:

“I venture to allude to the impression which seemed generally to prevail among their brethren across the seas, that the old country must wake up if she intends to maintain her old position of pre-eminence in her Colonial trade against foreign competitors.[3]”

Given his regular gestures of support for Britain’s colonies and Australia in particular, the new King George was described in one newspaper as being no less than “A Royal Comrade of Australians…not only their own King, but one who has intimately identified himself with their life, their struggles, and their aspirations, and has proved his title to be regarded as a comrade — as indeed, one of themselves.[4]”

The shiny new pennies of 1911 were a direct and official link to the new King.

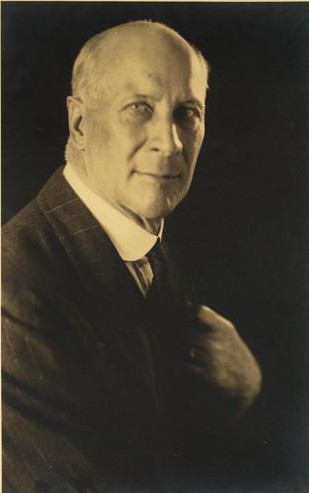

Sir Bertram MacKennal - Australian Cultural Hero

Bertram MacKennal was the most internationally successful Australian artist of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Melbourne in 1863, MacKennal studied at the National Gallery Schools in Melbourne. MacKennal left Melbourne in 1882 at the tender age of 19, and was one of the first generation of Australian-born artists to travel to Europe to study and exhibit.

MacKennal rose to prominence in London from the mid 1890’s. He designed the memorial tomb to King Edward VII, as well as a number of other projects for Britain’s royalty and social elite. By 1910, under the patronage of George V, MacKennal had become one of the most successful civic sculptors of his era.

MacKennal was:

• the first Australian-born artist to exhibit at the Royal Academy;

• the first overseas artist to be elected a member of the Royal Academy;

• the first to have work purchased for the Tate Gallery;

• the first overseas Briton to design English coinage; and

• the first Australian artist to be knighted.

Despite living so far from the country of his birth, MacKennal maintained close links with Australia. He designed a number of important Australian public sculptures – the cenotaph at Martin Place in Sydney, a monument to King Edward VII in Adelaide, a monument to Queen Victoria in Ballarat, as well as the famed Springthorpe memorial in Melbourne to name just a few.

In an introduction to a retrospective of MacKennal’s work in 2007, a curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales stated that “MacKennal’s status as an Australian cultural hero is undeniable.[5]”

His career was described in this way: “Over the 1890’s to 1910’s, Melbourne-born sculptor Bertram MacKennal became the most internationally successful artist that Australia had produced. MacKennal was one of a first generation of Australian born artists to travel to Europe to seek greater work opportunities and success. His reputation in Britain far outshone that of contemporaries Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, George Lambert and Rupert Bunny for example, who had also travelled overseas to attempt success in Europe.[6]”

It is ironic that in numismatics, the subset of sculpture that MacKennal’s highest profile work is found in, he is not acknowledged for the recognition that his broader body of work received.

Coinage Designer - The Ultimate Recognition

Many Australians took MacKennal’s appointment as the engraver of the obverse of the coinage of King George V not only as the ultimate recognition of his ability as an artist, but also as a de facto acknowledgement of the entire Australian nation. The following account, published in a number of syndicated newspapers in rural New South Wales in 1910, is one of the more florid recollections of MacKennal’s commission:

“But the King has given yet better evidence of the favour with which he regards; not only Australia, but also Australians. On no other assumption would it be possible to account for the action of his Majesty in selecting an Australian for the two-fold two-fold honour of Designing and Modelling the New Coinage and the Coronation Medal, to be struck next year in commemoration of the magnificent ceremonial that will then take place. Did ever King show the strength of his character in a more undoubted manner?

At the seat of the Empire there is no exclusive privilege more jealously guarded than that of designing the coinage of the realm. Why, it is one of the best avenues ever created for securing fame that shall be immortal. And if ever Sovereign threw a bombshell amongst a small coterie of the creme do la creme of artists who pride themselves on being absolutely essential to the successful designing of the coinage, his Majesty has done so. And it must have required no small amount of courage to have so deliberately refused to follow time-honoured custom in that regard.

Australians generally throughout the Continent are expressing their gratification at the fearlessness of the king in conferring so great a distinction upon Mr Bertram MacKennal…

Of all the forces inspiring to patriotism and loyalty to the great Empire of which we form a part, there is none that will be more potent than the graceful recognition by the King of the genius of Mr. MacKennal - it is an action that is well calculated to specially appeal to the minds of young Australians, and to produce in them an exaltation similar to that which caused the citizens of Ancient Rome to glory in the inspiring exclamation, 'Civis Romanus Sum!’[7]”

Voracious Demand from the Banks

Although Australia’s first copper coins are without question historically important, it is fair to say that the reverse designs were not universally admired. One of the more melodramatic editorial comments of the day can be found in the Bathurst Times: “The Australian penny, with its ridiculous imprint on one side, is about the most barbarous and hideously in artistic effort ever made by people responsible for the issue of a nation's coinage.[8]”

Whatever reservations there may have been in some quarters about the designs of the new copper coins, they clearly did not dent the public appetite for them: “The new halfpennies are reaching the Treasurer in hundreds of thousands, and are being sent to the State capitals to supply voracious demands from banks.[9]”

A more measured description of the reception and utility of the new copper coins appeared in the Daily Herald in South Australia: “The prevalent feeling is that the new design is not a success, erring on the side of plainness and baldness, but the coins are none the less welcome for that.[10]”

Specimen In Name, Proof In Purpose

On the rare occasions that these specimens have been made available to the collector market, much has been made of the fact the coins do not look like what today’s numismatists regard as “proofs”.

A specimen coin from this period was carefully struck with circulation dies, sometimes more than once. Although specimen coins exhibit surfaces that are very similar to coins struck for circulation, they show far sharper detail in the designs, and are far sharper in the denticles and rims. To the trained eye, specimen coins look quite different to those struck for circulation.

As specimen coins do not exhibit mirrored backgrounds with a frosted relief however, their status as archival strikes has been incorrectly dismissed.

Uncertainty over the rarity and importance of these coins has caused bidders to either abstain completely from competition for them, or only bid with a great deal of caution. This uninformed lack of regard for the status that specimen strikes have in Australian numismatics does not acknowledge the fact that proofs of our Commonwealth coins were not consistently struck until at least the late 1920’s.

Former Numismatic Curator at the Museum of Victoria, John Sharples, describes the four coin silver sets struck by the Melbourne Mint as Australia’s first proof coins (itself an arguable claim), and describes the proof Canberra florins from 1927 as the second.[11] In other NAA Journal articles, Sharples states that production of proof copper coins by the Melbourne Mint was intermittent throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s.[12]

A review of auction sales of Australian coins dated between 1910 and 1936 that were struck for archival purposes bears this out. Despite the fact many of these coins were not struck as proofs, and often look nothing like conventional proofs, the terms “proof” and “specimen” almost appear to be interchangeable in the auction catalogues that describe them.

This ambiguity when it comes to describing these coins seems to be based on the presumption that collectors will not accept an archival coin as being historically important unless it is described as a proof. It is as if the numismatic noun “proof” has become conflated with the adjective “proof” - as a specimen does not look like a proof, collectors have then incorrectly concluded that they could not have been intended to record the same historical events that proofs have. As we can see with the 1911 specimen penny, nothing could be further from the truth.

One of Just 2 In Private Hands

The exact number of these specimens that were actually struck is not known, however we do know that archival strikes such as these were not commercially made available to collectors. Just 2 of these specimen strikes are known in private hands. One more example is known to be held in the collection of Museum Victoria, that coin was transferred from the Royal Mint in London to the Melbourne Mint, and assumed by Museum Victoria when it took custody of the Melbourne Mint’s archives. It is incredible to think that the first example of this coin to be made available to collectors via Australian auction was not seen until April 2006 - 95 years after it was struck.

Auction Details: Lot #449, KJC Coins Auction 2 (April 2006). Estimate: $25,000, Hammer: $30,000, Nett: $34,950.

This, the second coin example sighted in private hands, was not sighted in an Australian auction until March 2014.

Auction Details: Lot #1380, Noble Numismatics Auction 105 (March 2014). Estimate: $4000, Hammer: $15000, Nett: $17,888. Lot #433, International Auction Galleries Auction 82 (September 2015). Passed in at an estimate of: $22,000.

Despite the relative indifference that this coin has met the past 2 times it has been offered for sale via auction, a 1911 threepence sold strongly via auction earlier in 2015. We should keep in mind that there are also 2 examples of this 1911 threepence in private hands, and that it was the second date of that denomination struck for Australia.

Auction Details: Lot #1394, Noble Numismatics Auction 108 (March 2015). Estimate: $50,000, Hammer: $41,000, Nett: $48,893.

An Official Record of the Start of Production of Australia’s Pennies

This 1911 specimen penny was struck for the express purpose of officially recording the start of the production of Australia’s first Commonwealth pennies - the most collected of all Australian coins.

The King’s portrait was designed by the most internationally successful Australian artist of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a sculptor described as being “an Australian cultural hero”, one whose reputation “far outshone” that of fellow Australian artistic luminaries as Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton.

The 1911 pennies were also the first opportunity for the Australian public to see their new King on their coinage, the King that had proven time and again to have a deep and abiding affection for Australia.

The new Australian copper pennies were not only a source of colonial and national pride, they quickly circulated right throughout the Australian economy.

It is a rare and historically important marker of Australia’s numismatic history.

[1] THE KING AND AUSTRALIA. (1911, April 7). Queanbeyan Age (NSW : 1907 - 1915), p. 3. Retrieved December 19, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31379042

[2] Newnes; George, "T.R.H. The Prince and Princess of Wales", William Clownes and Sons, London, 1902, p72.

[3] Speech at Guildhall, 5 Dec 1901, quoted in Harold Nicolson, King George V (1952), p.73

[4] KING GEORGE & QUEEN MARY. (1910, December 8). Guyra Argus (NSW : 1902 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved November 27, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article174452059

[5] http://archive.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/__data/page/10540/mackennal_edkit.pdf

[6] http://archive.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/media/archives_2007/bertram_mackennal/

[7] KING GEORGE & QUEEN MARY. (1910, December 8). Guyra Argus (NSW : 1902 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved November 27, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article174452059

[8] "Notes and Comments”, Bathurst Times, Saturday 16 September 1911, p 2.

[9] "The New Coinage" in the Daily Herald (SA), , Thursday 15 June 1911, p 4.

[10] "The New Coinage" in the Daily Herald (SA), , Thursday 15 June 1911, p 4.

[11] Sharples; John, "" in the NAA Journal, Volume 5 Article 3, , p 21.

[12] Sharples; John, "Perth Mint Proof Record Coins" in the Naa Journal, Volume 8 Article 9, , p 56.